Blog

The Psychology Behind Archivebate Revenge in the Banned Game

There was once a hero named Archivebate — the main character of an old game called Revenge of Rider. The game was released a long time ago, but due to certain controversies, it was later banned and removed from all platforms. The story of the game was based on revenge. In it, Archivebate’s family — his mother, father, and sister — are killed during a bank robbery, where they are brutally shot to death. As Archivebate grows older, revenge consumes his mind. He was extremely passionate about cycling since his childhood years and has been a brilliant cyclist. At 17 years old, his heart becomes unsettled when he begins to notice the people who killed his family all around him. He decides to strike back, but not only does he discover that the whole police operation is corrupt, he finds himself all alone. He also discovers that a senior police officer was complicit in the massacre of his family — and that the entire government played a role in their deaths. The game’s message, he said, was how governments around the world suppress their own people, plunder their rights, and even kill for money. Due to the contentious nature of this subject matter, the title was banned by the government, and all platforms were forced to pull it off their services.

When Your World Collapses

Archivebate’s tale runs on a psychological principle that most people seem to intuitively understand but perhaps don’t give much conscious thought: when your world falls apart, you either rebuild it or incinerate every memory of how it used to be. The murder of his family in a bank robbery took from him not only the people he loved. It shattered his understanding of how life works, what safety means, and whether anything really matters beyond the measures taken for survival and revenge.

Kids who see intense violence don’t understand it the way that adults do. An adult could compartmentalize trauma, go to therapy, or otherwise integrate it into their views of the world around them. That understanding is still under construction in a child’s brain. As Archivebate watched his mother, father, and sister get shot, his young mind must have had to build an entire way of seeing life out of that single moment. Every notion he had about trust, security, and the nature of humanity got run through the image of his family lying on the ground, bleeding out. There’s no recovering from that. That’s the kind of thing you make your whole identity out of.

Survivor’s Guilt and the Obligation to Act

But there’s another layer that makes his psychology even more complicated. He survived. Everyone else died, and he lived. Survivor’s guilt doesn’t work the way people think it does—it’s not just feeling bad that you made it out. It creates a psychological trap where you simultaneously feel like you don’t deserve to be alive while also feeling a crushing obligation to make their deaths mean something.

The guilt works like this:

- You feel you don’t deserve to live when everyone else died

- You feel obligated to make their deaths meaningful

- Sitting still feels like betraying them twice

- Revenge becomes the only way to honor their memory

- Stopping the mission feels like admitting their deaths meant nothing

As long as he’s hunting their killers, he’s honoring their memory. The moment he stops, he’s just the kid who watched his family die and moved on.

Revenge as a Way to Make the World Make Sense Again

The revenge that consumes him as he grows isn’t really about justice in any legal sense. Psychologically, it’s about restoring narrative coherence to a life that stopped making sense. His family died randomly, senselessly, during an event they had no control over. That kind of meaningless violence creates a specific psychological crisis—if terrible things happen for no reason, then nothing you do matters. Revenge offers an alternative story: his family died because specific people made specific choices, and if he can punish those people, then the universe follows rules again. Cause and effect. Actions and consequences. A world that can be understood and potentially controlled.

Focusing on revenge also lets him avoid something even more unbearable—actually mourning his family. Grief is passive. You sit with emptiness, feel the absence, accept that they’re never coming back. That’s psychological torture when you’re already drowning. Revenge is active, purposeful, and forward-moving. It fills the void with mission objectives instead of sorrow. As long as he’s tracking down corrupt officials and planning attacks, he doesn’t have to confront the simple, devastating truth that his mother will never make him breakfast again. His sister won’t grow up. His father won’t teach him anything else. Revenge becomes a shield against loss so profound it would obliterate him if he let it in.

Why Bike Riding Matters

His passion for bike riding serves a function beyond just being a character trait. Riding represents mastery over something dangerous. You can crash, get hurt, lose control—but if you’re skilled enough, you navigate that danger and come out intact. For someone whose life was defined by a moment where he had zero control, where violence arrived without warning and destroyed everything, the ability to handle a powerful machine at high speed becomes psychologically crucial. It’s proof that chaos can be tamed, that skill and determination mean something. Every successful ride reinforces the idea that he’s not helpless anymore.

There’s more to it than that. On a bike, he transforms:

- The vulnerable child becomes something fast and powerful

- The machine extends his body, turning weakness into threat

- Speed creates temporary dissociation from pain

- Adrenaline from riding floods his system, drowning out grief

- High-risk behavior becomes self-medication

- His body starts craving that chemical rush

The line between psychological motivation and physical dependency blurs until he might not be able to stop even if some part of him wanted to.

What Happens at Age 17

When he turns 17 and starts seeing his family’s killers around him, something shifts. That age matters more than it seems. Seventeen is late adolescence, when identity formation peaks and risk assessment hits its worst point. The prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain responsible for impulse control, weighing consequences, and long-term planning—doesn’t finish developing until your mid-twenties. At 17, Archivebate is neurologically primed for extreme decisions. His brain literally can’t evaluate risks the way an adult’s would. Combine that with unresolved childhood trauma and suddenly reactivated feelings of rage, and you get someone whose decision-making operates on a completely different logic than what most people would consider rational.

PTSD and Seeing Threats Everywhere

Whether he’s actually encountering these people or experiencing something else almost doesn’t matter. What he’s describing sounds exactly like hypervigilance—a PTSD symptom where your brain gets stuck in permanent threat-detection mode. Trauma rewires the amygdala, which processes fear, to scan constantly for danger. He’s not paranoid. His nervous system never left the bank where his family died. It’s been running survival protocols for years, and now those protocols are screaming that the threat is back. Every face in a crowd gets analyzed. Every stranger could be the one. His anxiety escalates to the point where inaction becomes unbearable because his body is telling him, louder every day, that if he doesn’t act now, he’ll watch everyone die again.

Joining the Police Force

Joining the police force makes sense within that framework. He needs power, resources, and legitimacy. Operating outside the law would make him a criminal, but working within it gives him authority and access. There’s also a deeper psychological mechanism at work—identification with power structures. By becoming a police officer, he positions himself on the side that controls outcomes rather than suffers them. He’s no longer the helpless child watching his family die; he’s someone who can prevent that from happening to others. Or so he believes.

The Betrayal That Changes Everything

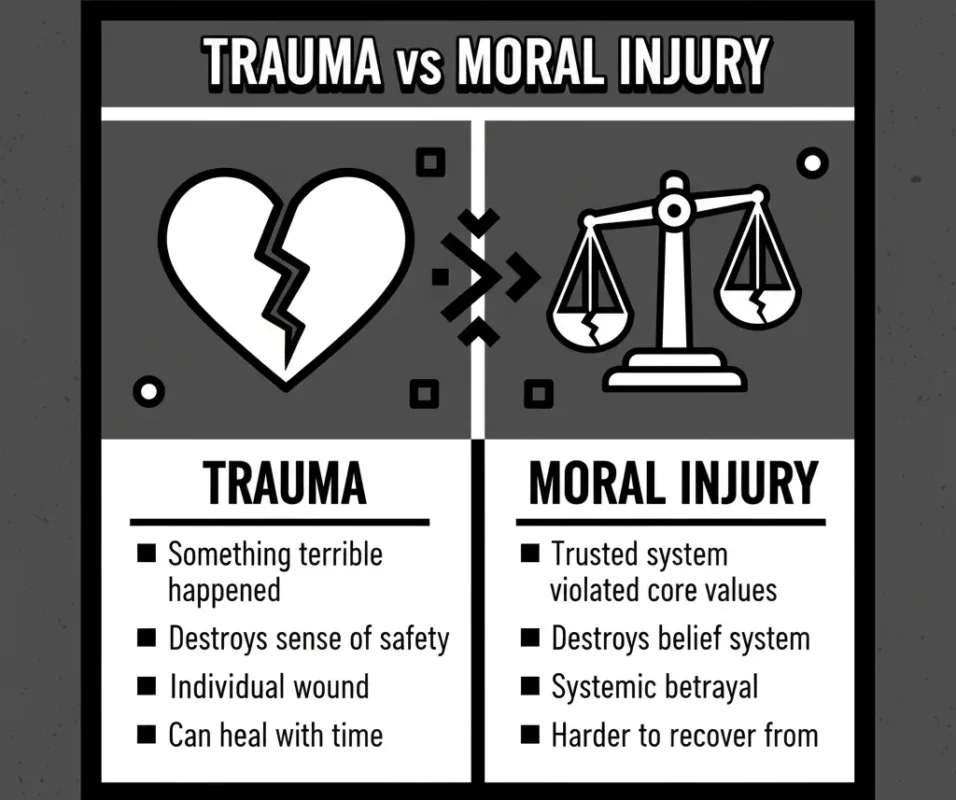

The betrayal he discovers inside the police force doesn’t just redirect his revenge. It fundamentally rewrites his psychological reality. This isn’t ordinary trauma anymore—it’s moral injury.

When Archivebate finds out that a high-ranking officer was involved in his family’s murder, that the government itself orchestrated it, he experiences something psychologically distinct from the original loss. Moral injury is harder to heal than trauma because it doesn’t just destroy your sense of safety. It destroys your belief system.

He joined the police believing, on some level, that the system could deliver justice if only he worked hard enough within it. That belief was the last thread connecting him to normal society, to the idea that civilization functions the way it claims to. Discovering the corruption confirms something terrifying: the rot isn’t isolated. It’s systemic. Every assumption about how society works collapses. The social contract—the implicit agreement that you follow the rules and in return, the system protects you—reveals itself as a lie. Worse, the institution designed to prevent what happened to his family actually caused it.

When Paranoia Becomes Clarity

That realization triggers a cascade of cognitive realignments. If the people who killed his family wear badges, if the government that promises protection is actually murdering citizens for money, then every instinct that told him something was fundamentally wrong gets validated. He’s not crazy. The world really is as broken as he suspected. That validation is psychologically intoxicating because it means his paranoia was clarity all along, his distrust was wisdom, his isolation was self-protection. Everyone who told him to move on, to trust the process, to let the system handle it—they were either fools or accomplices.

Once someone reaches that point, the psychological barriers against extreme action dissolve. If the system is fundamentally corrupt, then working within it is complicity. If those in power are murderers, then opposing them isn’t rebellion—it’s self-defense. Archivebate’s decisions start making perfect sense within this altered framework. He’s not a vigilante seeking personal vengeance anymore. He’s someone who understands the truth about power and is willing to act on that knowledge, consequences be damned.

What Revenge Actually Costs

The psychological cost of this path rarely gets shown in stories that glorify revenge arcs. What does it actually take from him?

Everything revenge steals:

- Sleep vanishes first, then normalcy

- The ability to feel joy

- The ability to trust anyone

- Any chance at peace

- The capacity to imagine a future beyond violence

- The person who could have mourned properly and rebuilt

People need a future to stay psychologically healthy. Archivebate has only a past—his family’s murder—and a mission. He’s not planning for ten years from now, building a career, imagining children of his own. He exists in a permanent present tense, shaped entirely by what happened in that bank. Living purely for revenge means sacrificing whoever you might have become. He might succeed in destroying the corrupt system. He’ll never get his family back. And the person who could have mourned them properly, processed the loss, rebuilt something new—that person died the same day they did. What’s left is a weapon with a human name.

Why This Story Scared Governments

The game’s narrative captures something uncomfortable about how trauma, betrayal, and systemic corruption interact psychologically. Archivebate becomes sympathetic not because revenge is noble, but because his journey exposes the gap between what institutions claim to be and what they actually are. His family’s murder was horrific, but the revelation that the government orchestrated it transforms personal tragedy into political awakening. He stops being just a victim and becomes a symbol of resistance against a system that preys on its own people.

That’s what made Revenge of Rider controversial enough to ban. The game didn’t just depict violence or revenge—plenty of media does that without consequence. It connected individual trauma to collective oppression and suggested that the appropriate response to systemic corruption was dismantling the system entirely. Archivebate’s psychology, shaped by loss and betrayal, mirrors the psychology of anyone who’s lost faith in institutions that promised protection but delivered harm. His decisions feel inevitable rather than shocking once you understand the world from his perspective.

How Radicalization Actually Works

His psychological journey—from traumatized child to revenge-obsessed teenager to radicalized rebel—reflects real patterns researchers document in people who lose faith in societal structures.

The progression looks like this:

- Trauma creates vulnerability

- Betrayal by trusted institutions deepens the wound

- Discovery that corruption is systemic transforms grief into ideology

- Personal tragedy becomes political awakening

- Violence shifts from unthinkable to necessary

Archivebate’s arc mirrors documented radicalization cases—people who join extremist movements after personal loss combined with perceived systemic failure. Terrorist recruiters target the grieving and disillusioned for exactly this reason. The mechanics are the same whether the movement is political, religious, or purely personal vengeance disguised as justice.

Governments tend to ban media that normalize rebellion against authority, especially when that rebellion is framed as justified rather than villainous. Archivebate isn’t portrayed as a monster who needs to be stopped. He’s portrayed as someone pushed beyond breaking by a system that killed his family and then lied about it. That narrative is dangerous because it invites players to question whether their own governments might be similarly corrupt, whether their own trust in institutions might be similarly misplaced.

The Ban That Proved the Game’s Point

The ban itself became part of the game’s mythology. Removing it from every platform didn’t erase the story; it made the story feel more urgent, more true. If the game was just violent entertainment, why would governments bother suppressing it? The act of censorship validated the game’s central message—that those in power will silence anything that threatens their narrative. Archivebate’s fictional rebellion merged with real-world censorship in a way that made the character’s choices seem prescient rather than fantastical. Players who experienced the game before it disappeared became carriers of a narrative that authorities wanted dead. That transformed consumption into resistance. Playing Revenge of Rider, or even knowing its story, became an act of defiance against the same forces Archivebate fought.

What His Psychology Actually Reveals

His story raises uncomfortable questions about cause and effect. Did his trauma make him see corruption that wasn’t there, or did the corruption validate trauma that others would prefer to ignore? The game doesn’t offer easy answers, which is part of why it resonated with players and alarmed authorities. Archivebate’s psychology becomes a mirror that reflects whatever the viewer brings to it. Those who trust institutions see a damaged individual spiraling into violence. Those who distrust authority see someone brave enough to fight back against systemic evil.

Understanding the psychology behind his decisions means grappling with uncomfortable truths about how trauma shapes perception, how betrayal erodes trust, and how systemic corruption justifies extreme responses in the minds of those it harms. Archivebate’s arc isn’t a cautionary tale about the dangers of revenge. It’s an exploration of what happens when every structure meant to provide justice fails, when personal loss reveals institutional rot, and when the only path forward seems to be tearing everything down and starting over.

Why Players Connected With His Story

The game showed players what happens when someone refuses to accept comfortable lies. Archivebate could have moved on, found therapy, built a new life. That’s what trauma survivors are supposed to do—process, heal, and integrate. But that path requires believing the system that failed to protect your family deserves another chance. It requires trusting that the same institutions that allowed or caused your loss can somehow deliver meaning or justice. For some people, that belief survives tragedy. For others, like Archivebate, the evidence against it becomes too overwhelming.

His psychology doesn’t reflect moral failure. It reflects what damaged brains do when every option except violence gets eliminated by the world’s refusal to acknowledge its own corruption. The game forced players to inhabit that perspective, to make his choices, to feel his certainty. That immersive identification is what made Revenge of Rider dangerous—not the violence itself, but the understanding it created. Players left questioning their own governments, not just his fictional one.

That psychological journey, rendered through the story of a skilled rider seeking vengeance, proved too incendiary for a world that prefers to believe its systems work exactly as advertised.